High Fen Wildland | Vision & Progress

By Matthew Hay, Natural Capital Manager, 25 June 2024

The baselining phase of our work at High Fen is coming to an end and we are now honing on in some of the interventions we want to enact to kick-start nature recovery across the site.

Central to this will be our peatland restoration project, which will see the return of that vital natural process, inundation, to parts of the site that are currently seasonally dry. Despite it being the wettest winter on record in East Anglia, by working with our fantastic hydrologist, Nick Haycock, we are going to use historical meteorological data to calibrate our water table depth for the year and understand how much higher it is than the average for the past 30 years.

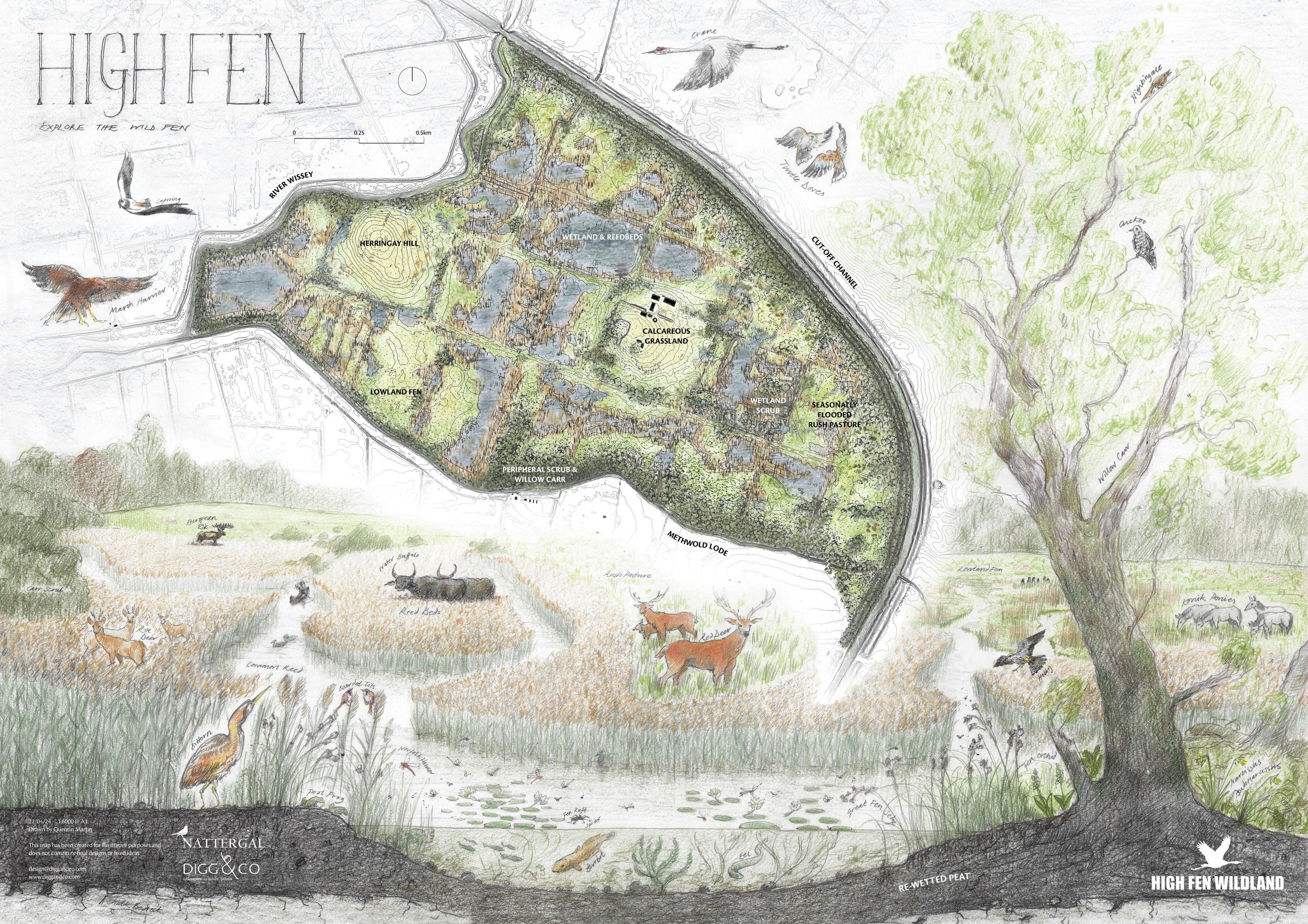

We’re then going to be installing several bunds – structures that prevent the lateral movement of water – in key places, to prevent High Fen’s groundwater draining into a huge channel that was dug by the Environment Agency in the 1950s, known locally as the Cut-Off Channel. If we can stop our groundwater draining away, then we’ll help to keep our surface water where it is, which will allow a whole suite of fenland habitats to emerge over time, including reedbeds, open meres, rush-pasture and carr.

At the same time, we’re planning to install a predator fence around the entire site, to help our wetland bird species recover. In 2011, High Fen had over 40 pairs of breeding lapwing and last year we had none at all. This is largely due to an increase in meso-predators in the Fens, with badgers in particular likely to be have had a big impact.

Without wolves and lynx in England, we’re missing the natural process of intra-guild predation, whereby apex predators target species like foxes and badgers, predating them both as food and to reduce competition for food. One radio-collared wolf from Slovenia, whose incredible 2,000km journey across the alps was tracked by biologists, largely sustained himself by eating foxes. For lynx, the proportion of their diet made up of meso-predators can be as high as 10%.

In the absence of this natural regulation, we will have to take action if we want our breeding cranes, marsh harriers, lapwing and redshank to thrive. With badgers being legally protected, our only option is to fence them out.

We’re keenly aware of the trade-off between this fencing and promoting ecological connectivity across the wider landscape. So we’re aiming for a structure that will be low enough for wild red, roe and Chinese water deer to jump, allowing these herbivores to still access High Fen and shape it with their wallowing, fraying, rutting and browsing.

Our overall objective at High Fen Wildland is to restore an abundance of life to a wetter, wilder, fenland landscape, primarily by getting the site’s hydrology right. To help distill our vision into something tangible and exciting, we worked with our friends at Digg & Co., who created the wonderful image below.

We look forward to making that vision a reality over the coming months and years, and hope you will continue to follow our progress from wherever you are!